I have long considered Jeremiah 20 to be one of the most transparent passages in all of Scripture. It is a chapter that contains the heart and soul of the prophet’s true self. Having been physically beaten by the priest Pashur and subsequently jailed, Jeremiah utters a prayer to God that is full of doubt and faith. These two things—doubt and faith—appear to be opposites at first glance. Often, we modern Christians tend to think they are incompatible. The truth is, though, they are not always mutually exclusive.

In his prayer, Jeremiah complains to God. He bewails his situation, questioning and doubting the goodness of God. He cries,

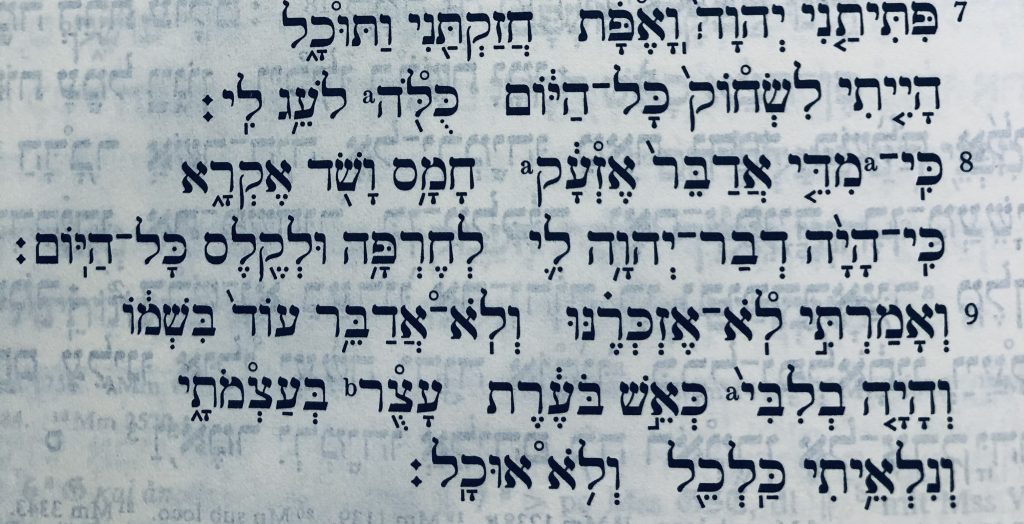

“O LORD, you have deceived me, and I was deceived; you are stronger than I, and you have prevailed. I have become a laughingstock all the day; everyone mocks me.”

Jeremiah 20:7 (ESV)

Then, just a few verses down, Jeremiah’s doubt is swallowed up with a moment of faith and confidence in his God. He says,

But the LORD is with me as a dread warrior; therefore my persecutors will stumble; they will not overcome me. They will be greatly shamed, for they will not succeed. Their eternal dishonor will never be forgotten.

Jer. 20:11 (ESV)

He continues in the next verse by expressing his faith in the God who will bring justice. Jeremiah knows God will come to his aid, saying to his Lord, “To you have I committed my cause” (v.12). Jeremiah then immediately breaks forth in praise, calling others to do the same. He sings,

Sing to the LORD; praise the LORD!

Jer. 20:13 (ESV)

For he has delivered the life of the needy from the hand of evildoers.

At this point, you might think Jeremiah has recovered his faith. You might come to the conclusion that Jeremiah’s sorrow has finally been remedied—vanquished and tossed into the abyss. If you think this, you’re wrong. In fact, Jeremiah’s doubt is still very present, wrapped in a garment of deep depression. After he uttered his last word in the praises of v.13 (see above), Jeremiah seems to have immediately lost it in the very next verse.

Cursed be the day on which I was born!

Jer. 20: 14-18 (ESV)

The day when my mother bore me, let it not be blessed!

Cursed be the man who brought the news to my father, “A son is born to you,” making him very glad. Let that man be like the cities that the LORD overthrew without pity; let him hear a cry in the morning and an alarm at noon, because he did not kill me in the womb; so my mother would have been my grave, and her womb forever great. Why did I come out from the womb to see toil and sorrow, and spend my days in shame?

Jeremiah does not wish he were dead. His sorrow runs deeper than that. He wishes he were never born. The prophet’s anger, despair, and depression all dance together in a mire of doubt. His questions reveal the disappointment he feels about the way his life has turned out. “Why did I come out from the womb to see toil and sorrow, and spend my days in shame?” (v.18).

I like Jeremiah because he is a lot like me (and perhaps you) at times: A mixed bag of praise and despair, faith and doubt, glory and cursing. Even though he has the ability to see that a new day is coming (e.g., Jer 29:11), he is not numb to the pain of the present (e.g., Jer 20:7-8).

Refusing all the clichés that plague modern evangelicalism, Jeremiah opts instead for honesty. Without pretension, he expresses the very real feelings of his soul: Grief, fear, pain, anger, confidence shame, faith, and doubt.

I continue to learn from Jeremiah. Life is seldom black and white. There is a lot of gray. The takeaway, I think, from Jeremiah’s curses and praises is that it is okay to describe our situations in life for what they are: Terrible and glorious—depending on the day.

The other thing to consider (and this might be hard pill to swallow for modern, Western Christians) is that our prayers to God do not have to be laced in niceties. Instead, they should be adorned with honesty. (Eugene Peterson spoke often about this. Hebrew prayer was anything but nice.) This is a significant observation to make because it can teach us something important about the relationship between faith and doubt. Notice, for instance, how Jeremiah takes his doubts about God to God in prayer: “O LORD, you have deceived me, and I was deceived” (v. 7). What this reveals is a principle about what it means to have true, living faith in God. The principle is this: Even our doubts about God can, if handled rightly, reveal our deep faith in God.

At first glance, it might appear that Jeremiah has deep doubts about God’s goodness. In truth, he does. However, because he feels the freedom to take such hard feelings to God, he reveals what he truly believes—namely, that God is strong enough to handle his doubts and loving enough to want Jeremiah to bring them to him. And it is this that Jeremiah believes. Ironically, then, Jeremiah’s doubts about God serve to reveal his faith in God.

Unbelief cannot always be chalked up to “having doubts about God.” Instead, true unbelief is failing to run to God with our doubts. Many Christians tend to do this. When they doubt God and when they encounter seasons pain and disappointment, they run from God. They quit praying, quit reading Scripture, quit going to church, quit worshiping. Why? Because they have never been taught that faithful prayers can be dirty, messy, and soaked in doubt. They were taught that prayer had to be pretty. And so out of fear that they will disrespect God by bringing their mess to him, they run from him. But Jeremiah was no modern-day evangelical. He was, instead, a believer in God.

As such, Jeremiah is a pastor’s pastor, indeed, a mentor for us all. He is a hero of the faith—even when he was full of doubt. He might have been an inspired prophet, but he was also a very broken human. And he was not afraid to show it (unlike most of us).

A few years ago, I scribbled a short poem about some of this, and I thought I would share it with you. The poem is about Jeremiah and about us. It’s about every person. Most of all, it is about Jesus, the man acquainted with grief and sorrow.

+ + +

“That Darkest Night”

Underneath fear’s pressing weight,

His hope, his life, they suffocate.

Dust for food in chaos grim,

Robbed of joy, the abyss to swim.

Thus Pashur in piety speaks

To Jeremiah’s soul; pain wreaks.

Happiness vanishes all too soon

As a phantom’s sprint; life’s poor ruse.

But just beyond that darkest night,

Is the King of dawn, burning bright.

Robed in his blood, our grief he bore,

He comes to make a world restored.